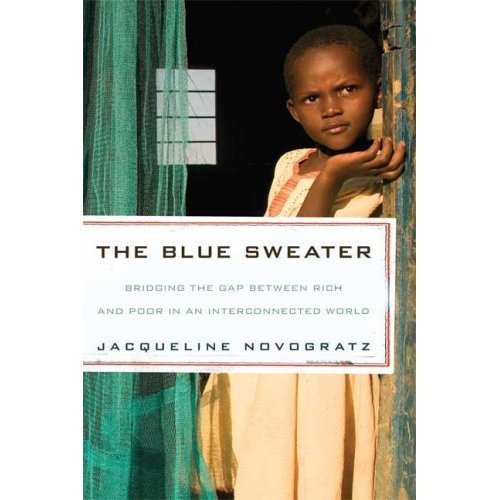

THE BLUE BAKERY by Jacqueline Novogratz

an abridged excerpt from The Blue Sweater:

Bridging the Gap Between Rich and Poor in an Interconnected World

“Poverty won’t allow him to lift up his head; dignity won’t allow him to bow it down.”

–MALAGASY PROVERB

THE 2-HOUR FLIGHT from Nairobi to Kigali begins over the wide-open expanse of the Kenyan savanna and ends among the mountains of Rwanda. I stared out of the plane’s window, enraptured by Africa’s shifting landscape, repeating the capital city’s simple, lyrical, and lovely name to myself: Kigali, Ki-ga-li. It rolled off my tongue like the hills that surround it. Kigali — it could be a woman’s name. I liked the sound of it.

We flew through a full blue-gray sky hovering over a tremendous charcoal river. Every inch of land was cultivated in neat squares of banana, sorghum, maize, coffee, and tea patched together by red dirt roads, like an enormous quilt in shades of green draped over the land.

On the 15-minute drive to town I saw flowers blooming everywhere. Square little houses in bright pinks and blues and yellows sat back from the roads, each with its own little garden. Billboards for condoms and soap, and face bleaching creams stood alongside the road, advertising goods the poor could spend money on to become whiter and more Western. And this was a country without television. In 1987, the consumer culture hadn’t even begun to penetrate it.

***

Honorata, a shy woman who worked with Veronique, told me about a project she’d helped create for single mothers in Nyamirambo. When [a woman] overheard, she whispered in my ear that the women were prostitutes. I shrugged but didn’t pay attention.

[We] drove into Nyamirambo. The day was hot; the air, heavy. Small shops stood one after another: tailors, hair salons, pharmacies, stores painted blue, green, yellow, orange. The unpaved side roads were filled with the burned-out bodies of ancient vehicles.

We passed a tailor shop, a clothing boutique, and a shoe repair store. Two doors down stood our destination: a singularly unimpressive gray cement building that housed Project AAEFR (Association Africaine pour des Entreprises Feminins du Rwanda).

All I could hear was my mother telling me that the path to hell is paved with good intentions. The detritus, disasters, and despair unwittingly created by well-intentioned people and institutions across Africa were evidence that my mother was right.

The group known as the Femmes Seules (code for unwed mothers) was one of many women’s groups organized in part by Honorata and Veronique’s Ministry for Family and Social Affairs. The women would gather for training and income generation. This particular group focused on a “baking project,” and sewing dresses on order. In a moment, it was clear to me that “income generation” was a misnomer. Only one woman was sewing at all; the rest were simply sitting quietly.

There were about twenty of them in the cramped front room all identically dressed in green gingham short-sleeved smocks. There were no baked goods to be seen and no sign advertised what the group did.

A solid, affable-looking woman named Prisca, dressed in the green checkered uniform, stood in front of the group.

“Welcome,” she said. “We’re happy you’ve come to visit.”

I thought of the word prostitute and the distancing power of language. Women with no money and few options are too easily categorized as throwaways. The poorest women in Africa often raise children while their husbands work in other places and their poverty sometimes causes them to sleep with a landlord when they can’t afford the rent. It is an act driven not by commerce but by the need for survival in a cruel market. I was infuriated by the license people felt to brand women who shared the dreams of everyone else.

After I introduced myself, the women shyly revealed their names: Marie-Rose, Gaudence, Josepha, Immaculata, Consolata — names that reminded me of doilies and lace.

I could see that the sewing project was going nowhere. I asked Prisca to help me understand the baked goods project.

“How much do the women earn?” I asked.

“Fifty francs a day,” Prisca responded, “and most are raising multiple children.”

“How much do you lose?”

Prisca took out the big green ledger in which she carefully recorded every franc spent, earned, and paid to the women. On average, the project was losing about $650 a month.

Six hundred and fifty dollars a month in charity to keep 20 women earning 50 cents a day. You could triple their incomes if you just gave them the money. It was a perfect illustration of why traditional charity too often fails: In this case, well-intentioned people gave poor women something “nice” to do, subsidized the project until there was no more money left, then moved on to a new idea.

“I’ll make a deal with you,” I said slowly. “If we drop the charity and run this as a business, I’ll help make it work.” I held out my hand. “Are you okay with this?”

Prisca lifted her left eyebrow in surprise. When she took my hand, she emphatically responded “Sana,” meaning “very much” in Swahili.

Our goals would be those of any business: to increase sales and cut costs. We’d start tomorrow, and we’d turn this project into a real enterprise with profits and losses.

We needed to increase the number of people we served. The only way I could think of achieving this was to go door-to-door. On that first, long day, we doubled the number of customers. We were in business.

Within several months, the project was profitable. More and more institutions signed up for deliveries, and the women began to see — for the first time in their lives — a real correlation between the effort they put into their work and the income they earned.

I shared with Prisca an idea I had to turn the little house in Nyamirambo into a real bakery from which we could sell our goods directly to neighborhood customers.

The first step was to give our building a fresh coat of paint — everything needed sprucing up. Consciously trying to learn to listen and not just hand out my own ideas, I insisted that the women choose the color themselves.

“What do you think?” they would ask.

One week, two weeks, three weeks passed. Each week, I asked the same question. Each week, I got nowhere.

Finally, at the end of the third week, I gave up, unable to take the waiting anymore. “What about blue?” I asked.

“Blue, blue, we love blue. Let’s do it blue.”

When painting day arrived, everyone turned out to help. The original idea was to paint the interior walls bright white and use the blue for trim. But this approach was not as satisfying as painting a wall blue like a morning sky. We even painted some of the windows blue.

A neighborhood crowd gathered to watch the phenomenon of women wielding blue paintbrushes. Onlookers munched on waffles and people danced in the street. Hips and paintbrushes moved to the rhythm.

After more than 8 straight hours of painting, we were finished. I joined the women outside in the street to look at what we’d accomplished. We were hot and hungry and covered in blue. For a minute we didn’t say a word.

It was so beautiful.

The color was perfect, I said. Most of the heads around me nodded in agreement — except for that of Gaudence.

“What?” I asked, one eyebrow raised.

“She thinks it is very nice,” Prisca translated, “but you know, Jacqueline, our color is green.”

***

The reality of our beautiful new bakery didn’t stop the setbacks, of course. One morning I walked into the offices at UNICEF and was told by a frantic office assistant that half of Kigali had called. “It seems that everyone in the city is suffering from eating the baked goods,” he said.

“What do you mean by ‘suffering’?” I asked.

He looked at the floor in embarrassment. “You know,” he said gently, “maybe they are having pains in their stomach, and many are going home sick.”

Feeling like Typhoid Mary, I drove quickly to the bakery.

“Everyone is sick with the runs,” I said. “Did you do anything differently?” They shook their heads.

“When did you last change the cooking oil?” I asked.

“Oh, never,” Josepha answered gleefully. “We have been adding just a little more each day. We are keeping costs low so that we can have high sales and more profit.”

Next lesson: quality control.

Within 8 months or so, the women were earning $2 a day — four times more than when we started together, and much more than most earned in Kigali; and in some weeks, they earned more than $3. Few people earned that kind of money in Rwanda, certainly not women. For the first time, their incomes allowed them to decide when to say yes and when to say no. Money is freedom and confidence and choice. And choice is dignity.

From THE BLUE SWEATER by Jacqueline Novogratz.

Copyright (c) 2009 by Jacqueline Novogratz.

Reprinted by arrangement with Rodale, Inc., Emmaus, PA 18098.

BUY THE BLUE SWEATER ON AMAZON

JACQUELINE NOVOGRATZ is the founder and CEO of Acumen Fund, a non-profit global venture fund that uses entrepreneurial approaches to solve the problems of poverty. Acumen Fund aims to create a world beyond poverty by investing in social enterprises, emerging leaders, and breakthrough ideas. Under Jacqueline’s leadership, Acumen Fund has invested more than $75 million in 70 companies in South Asia and Africa, all focused on delivering affordable healthcare, water, housing and energy to the poor. These companies have created and supported more than 57,000 jobs, leveraged an additional $360 million, and brought basic services to tens of millions. In December 2011, Acumen Fund and Jacqueline were on the cover of Forbes magazine as part of their feature on social innovation. Prior to Acumen Fund, Jacqueline founded and directed The Philanthropy Workshop and The Next Generation Leadership programs at the Rockefeller Foundation. She also founded Duterimbere, a micro-finance institution in Rwanda. She began her career in international banking with Chase Manhattan Bank.

Jacqueline currently sits on the advisory boards of MIT’s Legatum Center and the Harvard Business School Social Enterprise Initiative. She serves on the Aspen Institute Board of Trustees and the board of IDEO.org, and is a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the World Economic Forum Global Agenda Council for Social Innovation. She was also appointed by Secretary Clinton to the Department of State’s Foreign Affairs Policy Board.

She has been featured in Foreign Policy’s list of Top 100 Global Thinkers and The Daily Beast’s 25 Smartest People of the Decade. Jacqueline is a frequent speaker at forums including the Clinton Global Initiative, TED, and the Aspen Ideas Festival. Her best-selling memoir The Blue Sweater: Bridging the Gap Between Rich and Poor in an Interconnected World chronicles her quest to understand poverty and challenges readers to grant dignity to the poor and to rethink their engagement with the world.

She has an MBA from Stanford and a BA in Economics/International Relations from the University of Virginia. She has received honorary doctorates from the University of Notre Dame, Wofford College, Gettysburg College, and Fordham University as well the Freedom From Want Award from the Roosevelt Institute in 2011.

For more information on Acumen Fund, please visit www.acumenfund.org

Follow Jacqueline & Acumen Fund on twitter: @jnovogratz @acumenfund